Anisa Kline 2021 Field Report

2021 CLAG Field Study Award

Invisible and Uncounted: The Health and Lives of H-2A workers in Ohio

Invisible and Uncounted: The Health and Lives of H-2A workers in Ohio is a dissertation project focused on the H-2A population in Ohio. Its purpose is to obtain basic demographic information (age, sending region within Mexico, years in the H2A program, etc) about H-2A workers and also learn more about their occupational health, self-reported health and healthcare access. The projects looks for relationships between their work and living conditions on the one hand, and the health-related topics on the other. The intention is to identify the areas of greatest concern and generate information that is useful for policy, advocacy and farmworker support. This piece specifically focuses on information learned from participant observation at migrant health clinics and semi-structured interviews with stakeholders.

Keywords: H-2A, farmworkers, migrant health

The purpose of the research this summer was to learn more about the H-2A guestworker program and identify areas of concern that could then be focused on in a survey of H-2A workers. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with stakeholders, such as clinicians serving migrant populations or migrant rights’ advocates, and with government employees, such as housing inspectors with the state health department or investigators with the Department of Labor, in charge of administering and/or enforcing various aspects of the program. Participant observation was also conducted by volunteering at migrant health clinics and COVID vaccine events, and participating in the monthly virtual meetings of the Farmworkers Agencies Liaison Communications and Outreach Network (FALCON). The funds were spent primarily on gas, as both the migrant health clinic and the COVID vaccine events were 90-120 miles from my house. Funds were also spent on hotel stays when necessary and food and incidentals while in the field.

The migrant health clinic was held every Wednesday and is actually located on a large farm, Burrma Brothers, that employs H-2A workers. Although the doctor and the administrative assistant both spoke Spanish, the nurse did not, so I acted as a volunteer interpreter for her, interpreting for those patients who did not speak English. The experience was instructive on many levels. First, I simply spent time in an agricultural setting, observing the rhythm of the work outside our office (when people took lunch break, the bus that transported the workers to the different fields, etc). Secondly, in my role as interpreter, I interacted with some farmworkers, which gave me a chance to practice my Spanish and learn certain medical terms. Thirdly, the doctor was very supportive of my project, and he introduced me to a crew leader who supervised H-2A workers and one of the Buurma Brothers’ growers (which is a family owned business). The grower gave me a tour of the farm and spoke to me at length about his experience with H-2A workers. I learned that he only began hiring them a few years ago, because of pressure from ICE, and that he contracts with an FLC, whom he pays a flat rate to recruit, transport and supervise the H-2A workers. I also learned that this year, with the Biden administration, he has had H-2A workers disappear. That is, they simply use the visa program as a free and/or safer method of entering the United States, and once here, leave for other work. This experience is something I will be following up on in future interviews with other growers.

Also, the days at the clinic were extremely slow. One week we only had one person show up the entire day. Both the doctor and the woman at the front desk had been participating in this clinic for over a decade and they said that as the number of H-2A workers in the area increased, the number of visits to the clinic went down. The need is still there, since the doctor noted that during the 2020 season, when telehealth was the primary way he was seeing patients, he got many, many, calls from H-2A workers, but that never translated into in person visits in 2021. Healthcare access is one of the main foci of my research, so this data, even anecdotal, was interesting. I’ve spoken with two other clinicians at migrant health clinics and their experiences were different: patient volume was still roughly the same, even as the number of H-2A workers in the area increased. There are many possible reasons for this, but it points to, at the very least, variation within Ohio in terms of healthcare utilization by H-2A workers.

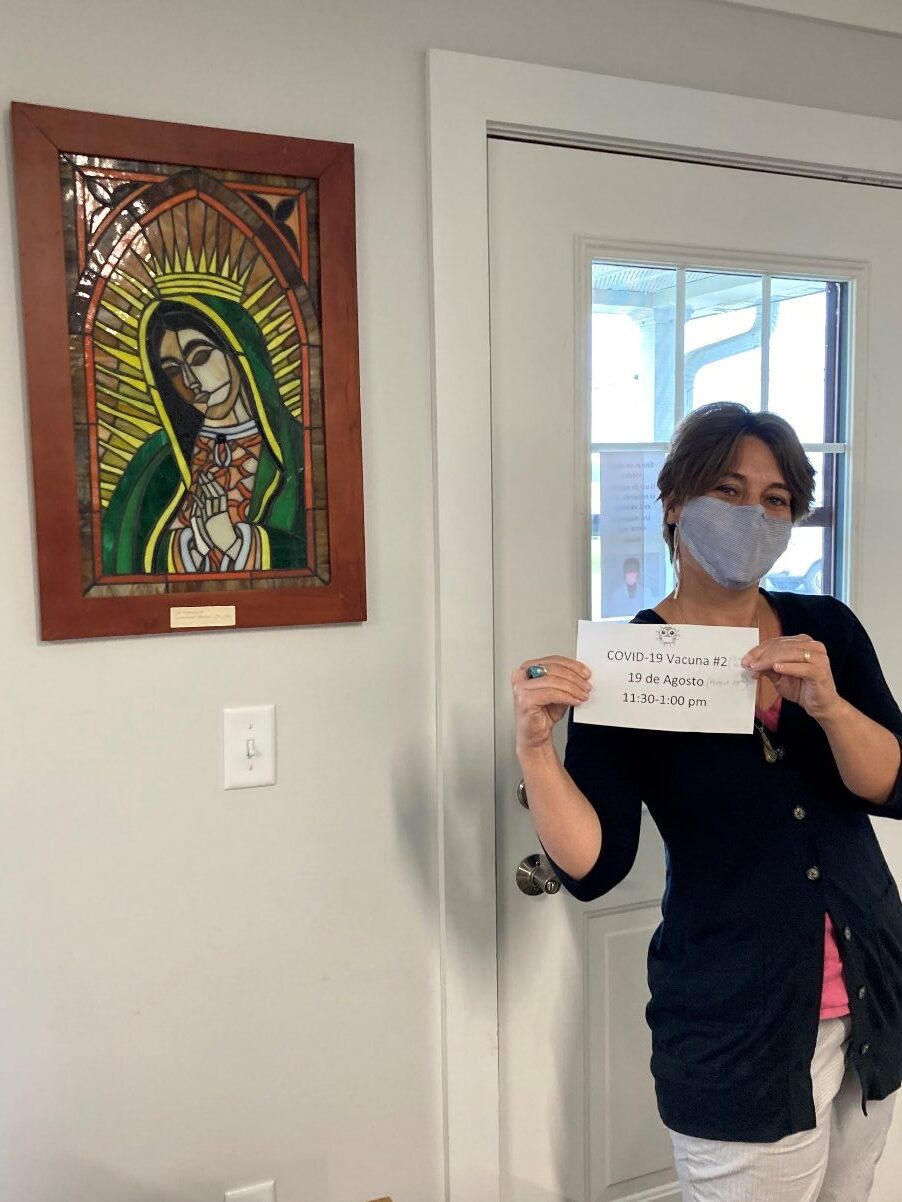

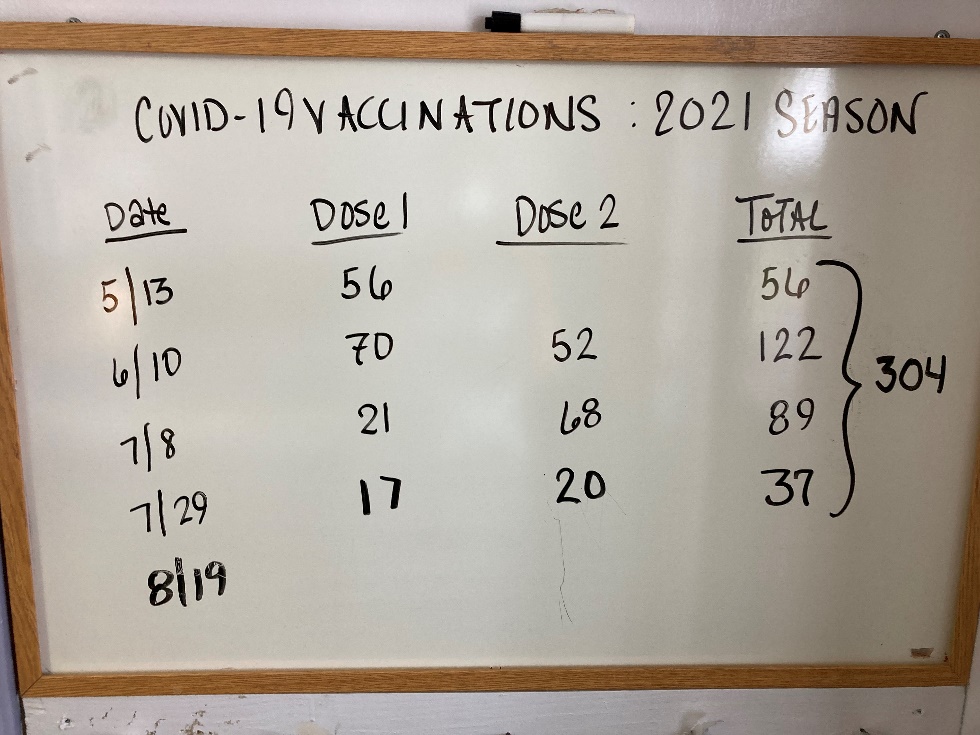

I also volunteered on two different occasions at COVID vaccine events at the Hartville Migrant Ministry health clinic, which is a migrant health clinic that operates as part of a small Christian nonprofit in Northeastern Ohio. Like the Community Health Services clinic, this clinic is on the property of a grower, and near many large farms (some, but not all of which employ H-2A workers). Again, the participant observation gave me a chance to interact with and become more familiar with the farmworker population in general and to observe firsthand the process of providing care to this population.

I also conducted semi-structured interviews with employees at the Ohio Department of Jobs and Family Services (ODJFS) who are in charge of administering the program, a lawyer and a paralegal with a legal aid organization, directors of various non-profits that provide support services for migrant farmworkers, and employees with the Department of Labor, including the community outreach coordinator and a senior policy analyst. Some of these interviews were done virtually, while others happened in person.

From these conversations, and my participant observation in the virtual monthly FALCON meetings and the meetings held by the Ohio Department of Health about coordinating a COVID vaccine effort for farmworkers, a few key themes emerged.

First, mobility is the primary challenge for this population. They simply can’t go places on their own and are therefore more isolated, hidden, and difficult to reach as a population. For example, the Hartville Migrant Ministry, which serves both H-2A and traditional migrant farmworkers, puts out free loaves of bread once a week for workers to pick up. The farm that employs H-2A workers does not permit them to make this excursion and so a volunteer must bring the bread to them. This kind of isolation directly affects healthcare access and the general perception is that no one knows how their health is because they’re not showing up in clinics. Family separation is the other big challenge, which has significant effects on the workers’ mental health and general wellbeing.

Another theme is labor control. For a variety of reasons, people feel that H2As’ movements are more constrained by their supervisors (above and beyond the questions of mobility) and they are also are less likely to complain about poor working conditions or wage theft than other migrant and seasonal agricultural workers. For example, the grower I spoke with told me that the FLC he hired told his workers they were not allowed to play soccer during their time off, since the worker might injure himself and the FLC would have to pay to transport him back to Mexico without having realized a return on his investment in bringing the worker here. The director of the Immigrant Workers’ Project told me that when a worker complains or quits he is often taken off “the list” of potential H-2A workers. However, in order to discourage further legal action, the employer will sometimes hire a relative of the erstwhile employee, and make it known that if the complaints continue, that relative will also lose their job.

I heard anecdotes from different sources about H-2A workers being denied healthcare by their employers (be it the grower or the Foreign Labor Contractor who is supervising them). In one case, a worker had attended a health clinic, gotten a vision screening and learned he was eligible for a free pair of glasses. However, he was never able to actually receive the glasses because the FLC refused to take him to the clinic to pick them up. In another case in southern Ohio, a handful of workers had gotten ill but the grower refused to take them to the doctor. Finally, when one worker’s condition worsened, the grower called his own family physician and requested that the doctor basically make a house call. Upon examining this worker, the doctor said he needed to be taken to the hospital and also warned the grower that he needed to provide more water and adequate breaks to his crew. Finally, one stakeholder, who also serves on the National Advisory Council for Migrant Health shared that when hearing testimony from H-2A workers across the country, one worker reported that a friend had gotten ill while working in the US, but was not allowed to go see a doctor. He worked through the season, intending to see a doctor when he returned home, but by then it was too late and the man died soon after returning home.

Although this is just anecdotal evidence, these conversations indicate that the H-2A workers do indeed face significant obstacles when trying to receive care. I believe this is just the tip of the iceberg so to speak- information gleaned over the course of one summer with a small sample of stakeholders. For me, it provides compelling motivation to continue this research, and points to the importance of conducting surveys and interviews with the workers themselves, which will be the next phase of my project.

Please see the print version for more details.